|

Photographic

Editions - Destroy the negative? Where's the value? Thoughts

and e-mail exchanges on the subject by Jean Ferro 6/24/03

between Jean Ferro, (intro and questions) (response) Stephen Perloff, Publisher

of The Photo Review / The Photograph Collector and Elizabeth Ferrer, Specialist

Mexican Art, along with an excerpt from Alex Novak, iPhoto Central on Vintage

collecting

In the early to mid-seventies, a photograph of Imogene Cunningham

was very affordable. At the time, photographers were always trying to find ways

to "increase" the value of their work. A photograph (price/value) did

not compare to a great painting or even a mediocre, one-of-a-kind painting. The

cost of producing the image and the selling price were very close to each other,

especially cibachrome prints and dye transfers. Lithographs

were among the most affordable and popular collectible. First, you had the artist

signed lithos and then, followed a supply of unsigned lithos. The artist would

create a limited 2nd generation edition from his original art work and then destroy

the plates that created the lithograph. Hence, one was left with a limited supply

of a 2nd generation image, the original and perhaps a couple of artists proofs. The

demand for multiple copies of a photographic image, because of it's popularity,

encouraged photographers to print according to demand or in some cases, create

completed numbered limited photographic editions. My recollection is that many

of the photographers during the early to mid-late 70's printed the full edition,

usually no larger than 25...and then "supposedly" retired the negative...for

LIFE..!

I remember it well because I was raising a young child and the

cost of edition printing was very expensive. The "type "R" print

was a disaster for a collector and was considered the "disappearing image."

Whether in a box, drawer or on the wall, the 1970's-80's "type R" color's

shifted into another dimension of unexpected color, so I printed "type'R's"

as test prints only, an inexpensive experiment to see the image enlarged from

the 35mm transparency. I kept thinking, I'll just choose one of my images and

make it an edition. This never happened because I could never decide which image

to make the heftiest investment in at the time. My recollection of the practice

of printing the full edition at one time seems shaded now that I'm hearing that

a lot of photographers just print on demand. At one time I had imagined myself

destroying the negatives after the edition was printed...actually, I still feel

that way, "X" amount of original prints and then that's it...ceremonial

destruction.

When WIPI recently collected our member photographs for

the WIPI/Palmquist/Yale collection,

I noticed an array of "limited edition" notations from 1/1 upwards to

80/300. Knowing some of these editions couldn't have been printed in their entirety,

I began to ask questions. Shortly thereafter, a couple of photographer buddies

went to the June Photo District News, "New Creative Vision Conference"

held in Los Angeles. They ventured into the conference seminar on "How To Get

Gallery Representation" with a panel of gallery owners who spoke on collecting.

They came away with the understanding that basically ... for a photograph to become

really valuable...the photographer has to leave the planet...! Obviously that

means he cannot produce the image himself or under his direction anymore...hence...

a very limited edition...! There

are varying techniques that photographers use to control the identity of their

work. Ansel Adams, according to his personal gallery, signed his prints when he

was the printer and initialed them when his assistant did the printing. He didn't

actually create limited editions, but rather created a special image to be included

in a specific limited edition of a book. A friend of mine, (who met Ansel at the

time in Ohio) has TWO of the very impressive books that contained actual photographic

prints. The listing reads: (On back of photo:) Fern Spring, Dusk Yosemite Valley,

California, CA 1961 by Ansel Adams An Original Photographic Print To Accompany

the De Luxe Edition of ANSEL ADAMS: IMAGES, 1923-1974 Published by the NEW YORK

GRAPHIC SOCIETY, LTD. Boston, 1974. This is Print Number CCXI (211) (the one book

has been opened to reveal the print inside and the other is CCX (210), never opened,

both are encased in their own beautiful black cloth case, with the engraved letters

AA. The print size, including mat is 13.5 X 16.5. It's impressive and feels so

important. You know you are holding something valuable in your hands, it's special,

not duplicable and signed by Ansel.  Ansel

also created a collection of prints that were from a selected group of images,

which became a set of limited edition portfolios. Some of the images included

in the portfolios would also be for sale -- independent of the grouping in the

book. The images chosen for the portfolio would not be produced again as a "specific"

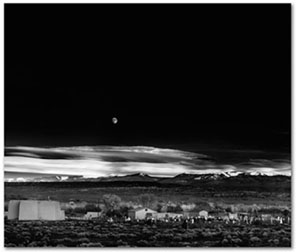

group of images. Interesting to note that Ansel's image "Moonrise, Hernandez

" may have a circulation approx. 900 upwards to 1200 prints according to

his gallery. So, I'm assuming from my e-mail from Stephen Perloff, publisher of

"The Photographic Collector" Newsletter, that earliest of the

Moonrise series would be the most valuable. Ansel

also created a collection of prints that were from a selected group of images,

which became a set of limited edition portfolios. Some of the images included

in the portfolios would also be for sale -- independent of the grouping in the

book. The images chosen for the portfolio would not be produced again as a "specific"

group of images. Interesting to note that Ansel's image "Moonrise, Hernandez

" may have a circulation approx. 900 upwards to 1200 prints according to

his gallery. So, I'm assuming from my e-mail from Stephen Perloff, publisher of

"The Photographic Collector" Newsletter, that earliest of the

Moonrise series would be the most valuable.

What

are the collectors looking for? Is it the image? The quality of the image? A time

period? Limited edition? A presentation similar to Ansel Adams? I understand,

a few years ago, a special collection of Cindy Sherman's self-portrait portfolios

sold at a $1,000,000 each to museums and collectors. I don't know how many images

were contained in the portfolios, nor the size or print types, or even if the

price quoted is correct...but it sounds good and I'm happy to hear that a contemporary

photographer can command high prices for their work.

Where does one

find guidelines about the ins and outs of print editions? Vintage, archival requirements?

And now what will all this mean due to the multiplicity of the digital printing

revolution? Now you have images on CDs, in various resolutions, easily printed

over and over. At least a dupe transparency was a generation away from the original.

It was very hard to get an exact dupe; there was always some negligible variation

that would distinguish the dupe from the original transparency. Sometimes this

difference wouldn't be noticeable to someone viewing the duped slide, but, put

the original and the dupe side by side and the difference would be very pronounced.

The duped image became a quest for the best labs in the world to produce a transparency

most exact to the original. At the time, I would label my transparencies "o"

for originals and all others were considered dupes. With digital printing, someone

can take your digital files and print a fine print that will last longer than

the conventional photo printing papers. Should

we as artists register the image with the copyright office as a way of signing

our signature to an original representation of our work? I wrote to the Photo

History group and received a couple of very interesting responses. Of course I

had a flood of questions to ask, and Stephen Perloff of The Photographic Collector

wrote back with some surprising responses. Several PRO photographers I asked personally

had a different take on the subject, all different and very variable... Perhaps,

in the end...it's the "image itself" that can spin the golden thread

of success in the eyes of the beholder and the world. Re:

[PhotoHistory] Photographic Editions - Destroy the negative?

An e-mail

request to the Photo History group, responses from Stephen Perloff, The Photographic

Collector and Elizabeth Ferrer, Specialist in Mexican Photography.

and Elizabeth Ferrer, Specialist in Mexican Photography. 1st

Response to Posting: STEPHEN PERLOFF, In a message dated 6/24/03 3:31:12 PM, info@photoreview.org

writes: JEAN

FERRO: Hello,

Is there someone on the list who knows the facts about:

Photographic editions?

Archival terms?

Vintage Prints?

There seems to be considerable

confusion on all subjects. Hopefully someone will have answers to all or any one

of the listed questions?

1) Are editions printed all at once? i.e.,

10/100, means 10th image of 100 printed at the same time? STEPHEN

PERLOFF: No - and this is problematic. Photographers often print five at a time

(say) to order and other than the most famous photographers who sell out an edition,

many editions are never completed. In fact, I contend that MORE photographs are

printed because of limited editions, since most photographers print a few and

then would prefer to move on. JEAN

FERRO: 2) Is there a specific time frame to print the edition? (i.e., so that

all the ink, chemicals, paper, tonal values are the same.) STEPHEN.

PERLOFF: No, though perhaps there should be, but in fact most photographers match

the print very well. Despite all the changes in papers, etc., these changes usually

take place very slowly. JEAN.

FERRO: 3) Is there a difference between the term "edition" and "limited edition"?

STEPHEN

PERLOFF: It's semantics. Is an edition of 500 limited? JEAN

FERRO: 4) For instance, could someone print their one image "edition of 300" over

time, and just number them as they go.? (printing from 1 year upwards to 5 - 10

years to print the complete edition? STEPHEN

PERLOFF: Certainly, though large editions are rare. I would prefer to see photographers

number their prints consecutively and date each with the negative and print date.

Of course, they'd have to keep good records. This would make earlier prints more

valuable. Instead the price of some editions rises as the edition goes on (say

each 5 prints cost more than the previous five). JEAN

FERRO: 5) Must the edition be printed on exactly the same paper, using the same

method of printing, not mixing various papers and changing to digital prints to

complete the 300 edition ?

STEPHEN PERLOFF: Of course. Some people have

made a new edition of sold-out images in a new size or medium.

JEAN FERRO:

...Using the SAME/EXACT negative/transparency/digital file: 6) Can there be several

different edition sizes? i.e., and an edition of 100 sized at 8x10? Another edition

of 25 of 11x14"? 3 of 20x24"?

STEPHEN PERLOFF: Yes. This is done by

some people, more usually in two sizes - large and Brobdinagian. JEAN

FERRO: Are there specific terms for a breakdown of this type? i.e., "Trees," 1990,

11" x 14" 2/25 of three variable editions? STEPHEN

PERLOFF: I haven't seen any consensus on this. It's usually an edition of 8 at

19"x19" and an edition of 4 at 44"x44". The listing (say in an auction catalogue)

would just be for that sized edition, e.g. 2/10. JEAN

FERRO: 7) How is a negative or transparency retired (without the photographer

dropping dead or destroying the original.) to guarantee it will no longer be printed

by the creator to protect the investment of the collector?

STEPHEN PERLOFF:

Only a handful of people have destroyed or canceled negatives. Usually it's just

trust and reputation. It would be hard to sell a new edition if you had a reputation

for "cheating." This brings up another problem. Limited editions benefit collectors

and sellers in the secondary market, but rarely the photographer. Only the most

famous photographers get to raise prices because an earlier edition sold out.

The profits are in the secondary market and in the US the artist never sees any

of that. JEAN

FERRO: 8) How many artists proofs are considered appropriate per image? STEPHEN

PERLOFF: I haven't seen any consensus here either, but it would be frowned upon

if an edition of 10 had 10 AP (artist proofs). JEAN

FERRO: 9) RE: Digital Editions, where do things stand in terms of digital files?

It changes yearly, if not monthly, regarding the range, brilliance and archival

property of inks and paper. So far the only "small" printer is the Epson 2000P

w/pigmented ink and archival paper, produces the most longevity of over 100 years

and maybe upwards to 200 years and it's largest print size is 13"x19". The 2000P

has a metamerism problem, which personally, I believe is an asset because it's

helps to identify the print longevity and stability. (which is becoming harder

to recognize with the vast amount of paper types now available).

The

2000P metamerism (color shift/hue cast in different lighting situations) seems

to only encourage more viewing to see the uniqueness of the color shift. Sounds

like a kinetic photograph! For anyone interested in "how archival is it?"....FYI:

Henry Wilhelm is the longevity print expert. http://www.wilhelm-research.com/

and works closely w/Nash Editions. Saw this recent article: (Wilhelm Imaging Research

paper titled: "Light-Induced and Thermally-Induced Yellowish Stain Formation in

Inkjet Prints and Traditional Chromogenic Color Photographs" presented at the

"Japan Hardcopy 2003" conference in Tokyo on June 12, 2003. The conference was

sponsored by The Imaging Society of Japan. It's always been my understanding that

an edition was printed "all at once," i.e., Lithographs (plates destroyed after

printing) and that an archival print was generally b/w produced on fiber paper

(silver gelatin). Now with digital printing associated to archival inks, and archival

paper, color will last as long as b/w fiber prints, maybe longer.

STEPHEN PERLOFF: I was just at a gallery that had to reprint and replace a 1999

digital edition because the color shifted. Soon digital prints will be more stable

even than silver and already can be more stable than a C-print. It will take a

while for collectors to adjust. Of course once you get the print you want, you

can set an assistant to make identical prints in large editions. Here again it

will be market forces and trust that control editions. JEAN

FERRO: Finally... 10) VINTAGE: What is the time span for something to be considered

vintage? Is it a print produced within 3 years after it was documented onto film...or

is this also another flexible area...and can it range from 3 years up to 10 years?

STEPHEN PERLOFF: This is even more complicated and I won't get into

all the variables here. But if the first print was made 10 years after the negative,

is that vintage? A 1950s Frank is worth more than a 1960s print is worth more

than a 1970s print. And certainly some photographers made "better" prints later.

JEAN FERRO: 11) What period of time has to lapse after the print date

for it to be considered vintage? STEPHEN

PERLOFF: It's not like a car. It's immediately vintage, though the term is not

really used for contemporary art. JEAN

FERRO: 11a) Is Polaroid considered vintage? STEPHEN

PERLOFF: By definition. JEAN

FERRO: Again, it's been my understanding that for an image to be considered vintage,

the original image would be produced using a choice of known film types, which

would then be produced on paper within a relatively short period of time to guarantee

the photographer's vision. The photographer was guesstimating that the photographed

image would be produced on the available materials (either old and available or

new at the time) they were familiar with, which in turn stimulated them to create

the original photographic project with the knowledge of the outcome and final

print. If they chose to deviate from the standard (manipulate in the darkroom

in some fashion), they were still working with the current materials that were

available at the time of the photographic project and close to the time frame

of image inception. STEPHEN

PERLOFF: Well, sometimes the photographer just chose what was at hand rather than

planning it all out. JEAN

FERRO: 12) OK...I know this is long, and even a suggestion of where to find the

info would be greatly appreciated. STEPHEN

PERLOFF: Read The Photograph Collector! (Oops, a commercial message.) JEAN

FERRO: As a photo artist I feel it's really valuable to be equipped with the knowledge

of the collectable marketplace.

Jean Ferro. President of Women In Photography

International

Stephen Perloff, Editor

The Photo Review /

The Photograph Collector

140 East Richardson Avenue, Suite 301 Langhorne,

PA 19047

Phone: 215/891-0214 Fax: 215/891-9358

E-Mail: info@photoreview.org

Website: http://www.photoreview.org

Any opinion expressed above is not that of my employer. Nor is it

even my own opinion. Any resemblance to an opinion held by any person, living

or dead, is purely coincidental.

The Photo Review is a critical journal

of national scope and international readership. Publishing since 1976, The

Photo Review covers photography events throughout the country and serves as

a central resource for the Mid-Atlantic region. With incisive reviews, exciting

portfolios, lively interviews, the latest in books and exhibitions, The Photo

Review quarterly journal has earned a reputation as one of the best serious

photography publications being produced today. Images:

Ansel Adams: Fern Spring, Dusk Yosemite Valley, California, CA 1961, De Luxe Edition

of ANSEL ADAMS: IMAGES, 1923-1974 Published by the NEW YORK GRAPHIC SOCIETY, LTD.

Boston, 1974.

Moonrise, Hernandez 1941 by Ansel Adams Website: www.anseladams.com Jean

Ferro S-P Collection: Death of the American Baby, Paris 1974

Jean Ferro S-P

Collection: The Green Slip, Paris 1974 (published Zoom Magazine editions:

Starting 1/28/84 France #110, England #26, Italy #47, Germany 1/85, first exhibited:

RIT invitational 1978 www.JeanFerro.com Note:

First complete Jean Ferro exhibition, printed by Paris Photo Lab w/Exhibition

poster, "Bomarzo" was shown w/sponsorship of Paris Photo Lab and Propaganda

Films in Hollywood, summer, 1989. Two sets of prints were made from work dated

1975-1987, most were transparencies and b/w negatives that had never been printed

before. One set remains (some images sold).

..sigh... The second set

of unsigned prints, while waiting for exhibition in Paris, France, "disappeared"

from the lab in Paris, The full set of Exhibition prints contained: 34 cibrachromes

ranging in size 13 x 19 1/2 down to 4 3/4 x 7" (includes 7 series groups)

and 13 silver gelatin, ranging in size 13 x 19 1/2 to 4 3/4 x 7", (includes

3 series groups ). Several of the images had been published in French Zoom, #110,

1985, 8 page layout.

Elizabeth

Ferrer, specialist in Mexican Photography reply: In

a message dated 6/25/03 2:21:25 PM, elizabeth_ferrer@yahoo.com

writes:

<<

I'd like to add to this discussion the point that things are quite different when

you are looking at photography out of the U.S./ European mainstream. I am a specialist

in Mexican photography, and it would have been quite rare in this country for

a photographer to create editions of their work up until the 1980s. At that point,

younger photographers, particularly those creating constructed or manipulated

imagery, began to introduce small editions. Some of the greatest Latin American

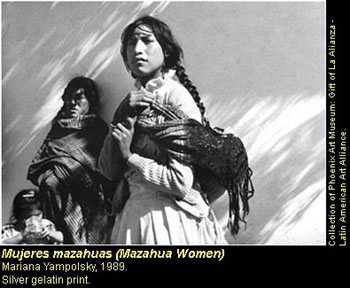

photographers, for example Manuel Alvarez Bravo or Mariana Yampolsky in Mexico,

never editioned their work. Who knows how many copies of Alvarez Bravo's La Buena

Fama Durmiendo are floating around? Certainly hundreds. That work was made in

1939, but there are prints of varying vintages (and values). In the case of Yampolsky,

her foundation is now numbering the posthumous editions, but none of the works

printed during her lifetime are numbered. <<

I'd like to add to this discussion the point that things are quite different when

you are looking at photography out of the U.S./ European mainstream. I am a specialist

in Mexican photography, and it would have been quite rare in this country for

a photographer to create editions of their work up until the 1980s. At that point,

younger photographers, particularly those creating constructed or manipulated

imagery, began to introduce small editions. Some of the greatest Latin American

photographers, for example Manuel Alvarez Bravo or Mariana Yampolsky in Mexico,

never editioned their work. Who knows how many copies of Alvarez Bravo's La Buena

Fama Durmiendo are floating around? Certainly hundreds. That work was made in

1939, but there are prints of varying vintages (and values). In the case of Yampolsky,

her foundation is now numbering the posthumous editions, but none of the works

printed during her lifetime are numbered.

Another issue to think about

when looking at photography outside the mainstream is economics. Photographers

often did not have the funds nor the supplies to produce an entire edition at

one time - they made a print when they needed to, for a show or a book or for

a sale. Up until fairly recently, many photographers from Latin American would

use trips to the U.S. to stock up on paper. That has largely changed, but I do

some work with a collective in Chiapas that still has to send their negatives

to Mexico City for high quality prints. So just throwing another element into

this discussion. I'm happy to address questions that relate to Mexican and Latino

photography, which to my knowledge have not appeared here previously. >> Elizabeth

Ferrer Mujeres

Mazahuas, collection from the Phoenix Art Museum at

http://www.phxart.org/yampolsky.html

Credit Line: Mariana Yampolsky, photographer,

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division

All images chosen to illustrate

the article were culled from private collections or public online display and

credited accordingly.

Alex Novak, Vintage

Works, Ltd. i Photo Central, http://www.iphotocentral.com/

an e-Zine for the collectors, images for sale, special events, collecting issues

& resources, eZine newsletter (Permission granted to use Information gleaned

from

(E-Photo

Newsletter Ê RE: : issue #57, A QUESTION OF VINTAGE AND DATING IN PRINTS AFTER

1955) E-Photo

Newsletter Ê issue 59 Ê 7/3/2003 Ê REVISITING: A QUESTION OF VINTAGE AND DATING

IN PRINTS AFTER 1955

Two newsletters ago I wrote the following article

and asked for response. I have recapped both the original piece and the responses

below. When we are talking about prints whose "vintage" quality or date is difficult

if not impossible to definitively ascertain by empirical means, I wonder how much

of a premium there should be on such an image. This is a specific problem with

images that were made mid-1950s through to today--some of the most currently popular

photographs with today's collectors. Is there meaning to "vintage" or even dating

of prints when this becomes impossible to prove scientifically as it is with many

prints made after 1955? Should all prints after this date be worth the same for

a given image? If not, why not?

This issue was particularly brought

home with the steep prices at the recent Seagram's sale for prints made largely

after 1955. Should a collector have to depend on the connoisseurship (or lack

thereof) of an auction house or a photo dealer to ascertain dating? Especially

in view of recent market scandals on this very issue (Lewis Hine, Man Ray and

others) involving some photo dealers (and auction houses), where "vintage" was

much more easily determined and was still inaccurately portrayed, however innocently?

While some of this "lack of knowledge" has been rectified, especially by AIPAD's

fine session on conservation techniques at the Metropolitan, there does not appear

to be similar techniques available for prints made after 1955 that work consistently.

Even provenance is not always a perfect solution, with artists themselves

and their heirs occasionally being less than accurate with the dating of prints.

I can cite at least four such instances that I personally encountered where the

photographer or heir inaccurately dated material by substantial margins or marked

it "vintage" when it clearly was not. It gets particularly problematic when heirs

date unsigned images that are made sometimes after 1955 when brighteners were

added to some commercial photography papers. It may then even be impossible to

know who exactly made that kind of print--another major problem.

Worse,

there are no guarantees in dating photographs at auction. Just read the various

auction house catalogues' fine print to see that you are only guaranteed that

IMAGES are by the photographers themselves (not even necessarily the prints).

This came as a shock to many during the Hine's scandal when prints were determined

by scientific methods to have been printed many decades after Hine had died. Today

these prints that were sold for tens of thousands of dollars in some cases have

little market value (a group of 14 of these prints dated 1973 by Phillips sold

at the Seagram's sale for under $800 a piece; which also makes one wonder what

might now happen to these prints). At least, as I understand it, the AIPAD photography

dealers who sold the Hines that were printed well after Hine's death were giving

money or credit back to their clients after the facts surfaced and the prints

went for testing. While occasionally auction houses may make allowances for inaccurate

catalogue information, they really don't have to do this because of their catalogue

exclusions.

As we enter a digital age, these questions will certainly

become even more important and may revolutionize how the photography market handles

the issue. It is important that the market deal with these issues forthrightly

in order to maintain the confidence of collectors and curators. I would appreciate

other viewpoints on this issue, and I will be happy to publish them in a subsequent

newsletter and/or on-line if fully attributed. Just email me at anovak@comcat.com.

If you have any information on editions in your country, please send it along

to: Info@womeninphotography.org

type "EDITIONS" in the subject area return

to WIPI News articles |